|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Britain’s Foreign Office engaged in “covert attacks” against the government of Ghana’s president Kwame Nkrumah, a recently declassified file reveals.

The objective was to create “an atmosphere” in which Nkrumah “could be overthrown and replaced by a more Western-oriented government”, the file shows. This policy was supported by officials in both Conservative and Labour governments alike.

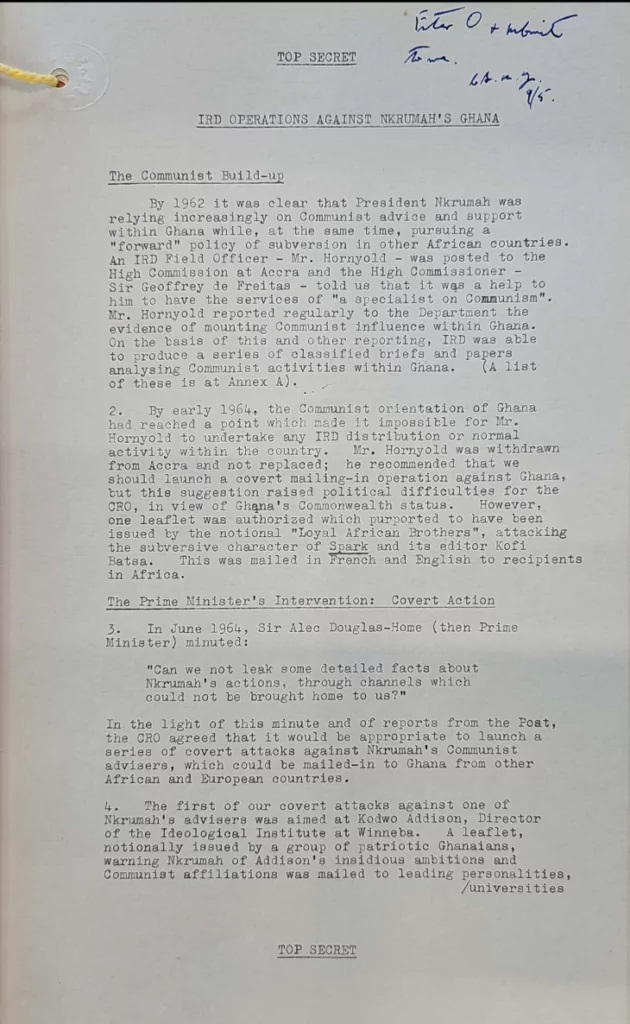

Marked “Top Secret”, the report was written on 6 May 1966 by the Foreign Office’s Cold War covert propaganda unit, known as the Information Research Department (IRD).

Nkrumah, a socialist and anti-imperialist revolutionary, was overthrown in a coup on 24 February 1966 by high-ranking elements of Ghana’s military and police.

The coup took place while Nkrumah was traveling to Hanoi to discuss proposals for ending the war in Vietnam. General Joseph Arthur Ankrah, deemed by British officials to be “nice but stupid”, replaced Nkrumah as head of the Ghanaian government.

The document, entitled “IRD operations against Nkrumah’s government”, is the most explicit proof to emerge so far of the UK pursuing regime change against Nkrumah.

A ‘more Western-oriented government’

Written by Sir John Ure, a career British diplomat who worked for the IRD for three years, the six-page report explains the IRD’s objectives in Ghana and the types of actions it took to help facilitate the coup.

“By 1962 it was clear that President Nkrumah was relying increasingly on Communist advice and support within Ghana while, at the same time, pursuing a ‘forward’ policy of subversion in other African countries,” Ure wrote.

He added: “The African, Editorial and Special Operations Sections of IRD have, throughout, worked in very close liaison over our treatment of Nkrumah’s Ghana; this treatment has aimed at contributing to the creation of an atmosphere in which Nkrumah could be overthrown and replaced by a more Western-oriented government.”

Ure concludes on a note which is as chilling as it is succinct: “Now that this objective has been realized, our efforts are being directed at ensuring that the lesson of Nkrumah’s flirtation with Communism is not lost on other Africans”.

‘IRD operations against Nkrumah’s government’

The IRD produced and mailed in thousands of leaflets from fictitious sources, published an average of one hostile article a month, and promoted anti-Communist books. All this was undertaken either on an “unattributable” basis or under the name of a fictitious Ghanaian group or movement.

Around 75 percent of Ghanaians lived in rural areas at the time, and Nkrumah was wildly popular with them. Yet it was not rural opinions that mattered to the IRD which sought to discredit Nkrumah amongst the influential members of the middle class and urban population.

IRD mail-in campaigns targeted a detailed list of librarians, teachers, training colleges, university educators, student groups, youth organisations, the press and police departments. Articles were also published in African Review, a publication secretly run by the IRD.

“The first of our covert attacks against one of Nkrumah’s advisers was aimed at Kodwo Addison, Director of the Ideological Institute at Winneba,” Ure explained in his IRD report.

This took the form of a “leaflet, notionally issued by a group of patriotic Ghanaians, warning Nkrumah of Addison’s insidious ambitions and Communist affiliations [which] was mailed to leading personalities, schools, youth organisations and the press”.

The IRD leaflet smearing Addison was soon followed by another “attacking” Kofi Batsa, the secretary general of the Pan-African Journalists Union.

‘Communist subversion’

From 1952 to 1957, Nkrumah led his country to formal independence from the British Empire, the first African country to do so. He became Ghana’s first post-independence prime minister and was in 1960 elected president.

One of the most outspoken proponents of Pan-Africanism, Nkrumah co-founded the Organisation of African Unity in 1963 which became the African Union in 2002.

As president, Nkrumah granted safe haven to activists and resistance fighters from across the continent and provided financial and military support to Africans engaged in wars of liberation, notably in the Portuguese colonies of Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique and Angola.

Nkrumah’s government also pursued a more confrontational approach towards the white supremacist regimes in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and South Africa, which the UK found problematic due to the substantial level of trade that it conducted in southern Africa.

Internal Foreign Office documents refer to Nkrumah’s anti-colonial agenda as “subversive activities”.

A ‘series of covert attacks’

UK propaganda efforts against Nkrumah and the governing Convention People’s Party (CPP) accelerated substantially in the last few years of his government.

In June 1964, prime minister Sir Alec Douglas-Home drafted a minute asking: “Can we not leak some detailed facts about Nkrumah’s actions, through channels which could not be brought home to us?”

The Commonwealth Relations Office (CRO) “agreed that it would be appropriate to launch a series of covert [propaganda] attacks against Nkrumah’s Communist advisers, which could be mailed-in to Ghana from other African and European countries”.

The 1960s was a period of crisis for Ghana. Nkrumah survived multiple assassination attempts, including bomb attacks between 1962 and 1964. Dozens of civilians, including at least 12 school children, were killed in a series of bombings in 1963, and over 20 people were killed in 1964 during a CPP rally.

Although Nkrumah remained popular with large swathes of the population, his government became increasingly authoritarian, particularly against its critics. In 1964 he was declared president for life and Ghana became a one-party state, banning all opposition parties.

“About every two years we are asked to help Ghanaian plotters to get rid of Nkrumah,” Britain’s high commissioner in Accra, Arthur Snelling, wrote in a 1965 top secret document.

Although these coup plots dated at least as far back as 1961, at no point does it seem that the British informed Nkrumah about any of them, even though Ghana was a member of the Commonwealth.

‘The last stage of imperialism’

Ure’s report also shows how Nkrumah’s book, Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism, published in 1965, infuriated the British and led to them escalating their attacks.

“[I]t was only after the publication of Nkrumah’s book on ‘Neo-colonialism’ in October 1965, that we were advised by the CRO that we need no longer be inhibited by Ghana’s membership of the Commonwealth”, wrote Ure.

He added: “We consequently began to include more material on Ghana and Nkrumah himself in our normal output, the main vehicle still being the ‘African Review’.”

In his book, Nkrumah blasted the exploitation of African nations by Western governments, intelligence agencies – especially the CIA, financial and investment companies, oil and mining corporations, and ‘aid’ agencies such as the IMF and the World Bank.

“The essence of neo-colonialism is that the State which is subject to it is, in theory, independent and has all the outward trappings of international sovereignty”, Nkrumah explained. “In reality its economic system and thus its political policy is directed from outside.”

While the role of the CIA in the 1966 coup has been covered, Britain’s role has remained more opaque.

It was known the British opposed Nkrumah, preferred that he be replaced and engaged in covert propaganda against his government. This fact was most recently detailed by Susan Williams, the author of the well-researched, White Malice: The CIA and the Covert Recolonisation of Africa.

The post-coup military junta delighted British diplomats, who described it as “strongly anti-Communist”. US officials were equally as pleased and cheerfully characterised it as “almost pathetically pro-Western”.

Sir John Ure would go on to serve as British ambassador to Cuba, Brazil and Sweden, and died last year.