|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

James Barnor is in Paris looking through negatives and old photographs, some of which he hasn’t seen since he took them more than 50 years ago.

There’s one of a young Ghanaian couple on their wedding day, others of a boxer preparing for his fight, a girl proudly holding her birthday cake.

“I have lost a lot with all my toing and froing, so when I come across some that I haven’t lost, and it is iconic and I have a story about it … Oooh,” he exhales. “I want to take the one who found it and squeeze her!”

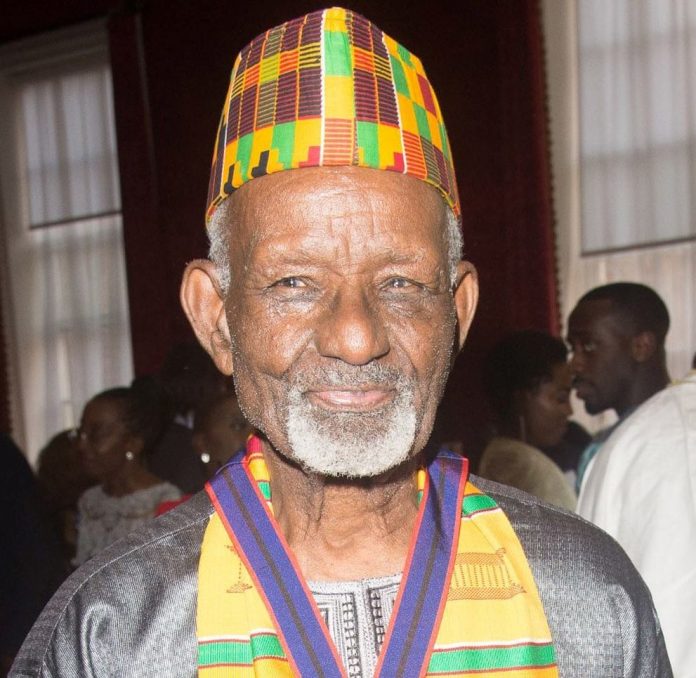

Barnor, who is 90, has produced some of the most memorable records of Ghana’s push towards independence in the 1950s, as well as capturing an alternative perspective on the swinging 60s in London, focusing on the experience of the African diaspora and bringing black models into mainstream British media. But despite his significant contribution to the culture and history of both Ghana and Britain, he was relatively unknown until recently. Now, he boasts a following on Instagram and has exhibited globally; this year, his work will be in three galleries in Paris and at the newly opened Nubuke Foundation in the Ghanaian capital of Accra, where he was born. It has taken a lifetime, but he is proud that his art is finally reaching a wide audience.

Nubuke curator Bianca Manu thinks the appetite for Barnor’s work is due, in part, to the growing appreciation of African photography as visual art, along with Ghana’s growth and development. “People want to know how we reached this point,” she says. “Who were the pioneers.”

It’s the first time Ghana has hosted a retrospective of a homegrown photographer. Barnor thinks Ghanaian photographers are not opening up their work for others to see. “You should share ideas and not be afraid of your fellow photographers. We fear that if we share ideas, they will get your style, your knowledge – if not your customers – so everybody keeps to themselves and doesn’t share.”

Barnor started out as a photographer in the late 40s, and says: “I had a focus and I was ambitious.” In 1947, he set up his own studio, Ever Young, in the Jamestown district of Accra, taking portraits of the local community. Two years later, he became the first photojournalist to work at the Daily Graphic newspaper (now state-owned, it was brought to Accra by the Daily Mail’s Cecil King), where he covered everything from local news and sports to politics. “I could do my own stories when I took pictures, without a reporter,” he says. “I often worked not on assignment, [but] leading my own story … and got it published.” At that time in Accra, he says, photographers weren’t working with reporters to cover the news. “I was the first.”

Barnor’s keen eye for a good story led him to document Ghana at a time of incredible transformation. Also working for Drum magazine – South Africa’s influential anti-apartheid journal for politics and lifestyle – his images show a country coming to terms with the modern world; visible in the explosion of fashion, art and music being enjoyed on the street and in overflowing bars. He photographed key political figures such as the country’s first prime minister, Kwame Nkrumah, and covered Ghana’s independence from the UK in 1957. “It was exciting and I was in the middle of it! When I covered independence day, I saw other foreign press with expensive new cameras – two or three each – and I was there with a little inexpensive camera. But with luck I got some assignments and I got good pictures, so I feel proud.”

Barnor’s work is credited with helping to “decolonise” Ghana, but he says there is still some way to go. “Culturally, we are not there yet. We should be mindful of who we are and what we should develop. But people are thinking of money and other things, not of culture,” he says. “People think they have been put in this position to enjoy money and power and not be the servant of the people.”

Barnor moved to London in 1959, and found a country at the dawn of another kind of revolution. Across Britain, the grey, postwar years were being coloured in with a youth-driven counterculture with mind expansion and nonconformity at its centre. The capital was a burgeoning multicultural city. “Normally, black people move to London or England and they struggle before they make it – if they make it at all. They get colour discrimination or whatever you call it,” he says, but admits his experience was quite different.

Barnor’s association with Dennis Kemp, whom he’d met in Accra and who worked for Kodak Lecture Service, opened up a world for him. He worked for Kemp at KLS in return for board and lodging and lived at Kemp’s flat in Holborn. Later, Barnor learned colour photography at Colour Processing Laboratories in Kent and did a two-year course at Medway College of Design. Barnor was an enthusiastic student absorbing all the training that was on offer to him, just as he had been an enthusiastic reporter, throwing himself into every assignment given to him.

All the while, he was shooting for Jim Bailey of Drum magazine, which put black British models on its covers (before Barnor, Drum had only ever shot models in South Africa) and photographing people such as Muhammad Ali and BBC news presenter Mike Eghan. Though he mostly worked on commission, Barnor also took pictures for himself, photographing friends and family, as well as the Ghanaian communities of London.

Educating others has always been a central part of Barnor’s life, and during his 10 years in England he was determined to bring what he had learned back home. Barnor opened the first colour processing laboratory in Ghana, working as a representative for Agfa-Gevaert, and was one of the first to shoot Ghana in colour. Combing knowledge of the printing process and an eye for composition and content, he produced a vivid record of the country’s post-independence atmosphere of the 1970s.

“I came across a magazine with an inscription that said, ‘A civilisation flourishes when men plant trees under which they themselves never sit.’ But it’s not only plants – putting something in somebody’s life, a young person’s life, is the same as planting a tree that you will not cut and sell. That has helped me a lot in my work,” he says. “Sometimes the more you give, the more you get. That’s why I’m still going at 90!”

Barnor spent the next 24 years in Ghana, struggling to make a living before returning to England to find that much had changed. “I was a cleaner in schools and at Heathrow airport,” he says. “I was 60 and nearing pensionable age, and already photography was not the same as it had been: everybody could use a small camera. Even the colour processing lab said the Japanese invasion had spoiled their work.” But after his images were shown at Acton Arts Forum in the early 2000s, he decided to put together an exhibition of his own. On his 80th birthday, Barnor filled Acton Town Hall with his prints and invited the Ghana high commissioner to attend. “It went in the African Voice and that’s how ‘James Barnor’ got on to Google for the first time,” he says.

With several decades of rich archive, and exhibitions around the world, you could hardly blame Barnor if he wanted to retire, but putting up his feet isn’t going to happen any time soon. He travelled to Paris to help scan images and write the shows’ captions. “It’s important that I do it. It’s not a holiday. I only regard it as a holiday because when I find a new picture, I’m over the moon.”

Source: The Guardian